Student Travel | Reflections on a European War Tour

I’m just back from leading a “European War Tour” that took me and my group from California from the beaches of Normandy via Paris, Belleau Wood, the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge), Nuremberg, and Buchenwald Concentration Camp, to Berlin. It was a fascinating, packed trip. It had me, someone who has visited many World War related sites, thinking deeply and reflecting.

The most obvious reflection is of course the loss of life and the suffering and sacrifice of the people involved. I reeled off numbers like 6,600 US losses on D-Day, 6.2 million Jewish deaths, 50 million overall casualties, without ever being able to think of what this actually represents. We simply cannot picture numbers like this. It was only by reducing the statistics to statements such as “80 men died at the Somme for each yard of land captured. That’s two of these buses filled full of young men for every single yard, before we reach the 1 million total who died in taking the 4.5 mile gain in territory.” Even then the scale is just so hard to grasp.

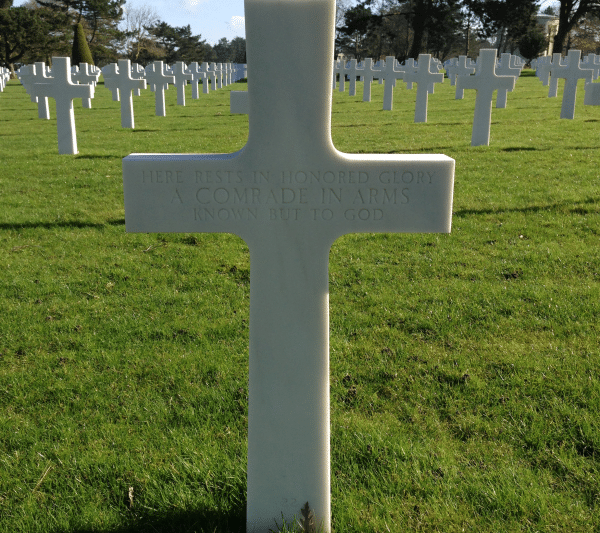

We visited a number of war cemeteries which helped in some way with the issue. The US cemeteries looked like a sea of white crosses (peppered with occasional Stars of David). They are always immaculately kept: pristine, peaceful, proud and perfect. I encouraged everyone to realise that each person here had a story; they should look at the name and the state and reflect on the fact that each one had a childhood, a family, friends, a personal history. Many were not much older than the students in the group at the time of their death. The US memorials included maps about the campaigns and inscriptions with at times somewhat dramatic language. It was hard not to think there was some kind of political purpose behind parts of the design, even if the major purpose was clearly the remembrance of the individual.

It was not just US cemeteries that we saw. We also went to a German and a Soviet war graveyard, where we reflected on the entirely different feel of the places. The German cemetery was sombre and sorrowful. It too was beautifully kept, but this was clearly no victor’s creation. Where visitors to the US cemetery could be drawn into the proud inscriptions about sacrifice for the greater good, the German dead offered no such comfort for the visitor or family member. The graves were doubled up and marked by simple grey stones on the ground. The Soviet war cemetery in Berlin was different again: it was a highly overt piece of political propaganda. At the entrance was a sculpture from stone taken from Hitler’s bunker and at the end of the site was a colossal statue of a Red Army sergeant with a little German girl he had saved in his arms (a true story). This was all about collective sacrfice, there was no element at all of individual remembrance as at the German or the US cemeteries. The dead here had no separate stones: they were buried in big trenches that were then covered over.

I reflected too on the way we still see history very much through our own prism. British war movies concentrate on how clever we were in outwitting the oafish Germans. We broke their secret codes, we invented the bouncing bomb, we broke out of Colditz Castle. Our “Keep Calm and Carry On” attitude is shown in photographs of milkmen carrying out their deliveries through bomb torn streets in London. The American WW2 War Memorial in Washington carries the dates “1941-45.” Movies tend to focus on D-Day, the Normandy landings and the Battle of the Bulge. The Soviet War Cemetery too carried the dates “1941-45,” which conveniently forgets that Soviet troops actually entered the war on the Nazi side on 17 September 1939. This was the day they invaded Poland, followed later by their invasion of Finland and the Baltic States. The way the Russians look back on the War is entirely different to how we do: for them it was a struggle to the death between the socialist Motherland and the fascist Nazi beast, fought and paid for almost entirely with their blood alone.

This “prism focus” is of course very common. There is apparently an African saying along the lines of “Tales of hunting will always glorify the hunter, until the lion gets his own story-teller.” It depends who is telling the story as to which angle it will take. I remember for example learning about the “American War of Independence” at school and was quite surprised when someone in one of my groups called it the “American Revolution.” I’d never seen it in that way. In a similar vein, British history has labelled Catholic Queen Mary as “Bloody Mary” for eternity, whilst her Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth I has gone down as “Good Queen Bess.” An almost identical number of religious deaths occurred during both reigns, and even though Elizabeth ruled longer, this is hardly ever focused upon in British schools.

It is also very natural (and indeed right) for us to remember our own fallen. The US Marines’ sacrifice at Beleau Wood during WW1 was the bloodiest battle they had been involved in. It has entered US military lore, despite the fact that the number of deaths was actually very small. 1811 men died here, compared to 1 million British, French and Germans who died at the Battle of the Somme. Of course it matters more to Americans because they have a connection of nationality and perhaps even are relatives of those who fought.

However, if we wish to gain a more objective, overall view of historical events, our own “prism” view can be a hindrance. My group was surprised when I told them the Normandy landings did not even feature in the top 8 battles of WW2. Seven of the top eight were actually fought in the East, between the Soviets and the Germans. Both British and US total military losses were less than 1% of the total of WW2 casualties. The Germans lost over 80% of their casualties on the Eastern Front, yet our “European War Tour” didn’t even feature more than a passing mention of the Battles of Kiev, Leningrad, Stalingrad and the Barbarossa campaign. If anyone can be excused for having a narrow view on the importance of their contribution, it would in fact be the Soviets, with 14 million military war dead.

From a civilian perspective, the British painfully remember the 45,000 civilians killed in the London Blitz (0.1% our population), yet remarkably few of us consider that Poland lost 6 million civilians from 1939-45 (20% of its population) or that Belorussia suffered even worse. A staggering 1 in 4 of its people were killed during WW2.

A related, further perspective, however, is that history is not a competition. This is particularly the case when we are talking about deaths and suffering. Each death, and each family loss is a tragedy and it would offensive to suggest any matters more of less than any other. The Soviets did pay far more heavily than anyone else in terms of casualties, but to the elderly Dane who still mourns the loss of his brother, amongst the 16 Danish soliders who died fighting the surprise German invasion, this is little personal consolation. The contributions from all Allied countries all played a linked and important part in victory. It was not just deaths, but also industrial, financial and strategic contributions that helped win both World Wars in Europe.

(Visiting American fox holes from the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes: as featured in Band of Brothers)

The study of the World Wars, their causes, and their results, is one of the most important things I can think of in history. It fascinates me, it upsets me, it makes me reflect, and I hope it teaches me. It is a wonderful thing that so many decades after the events, schools are signing up for student travel and coming on these trips to learn more about them. I am still processing much of this: I hope that when the students have gained a new perspective and that the places they have visited will bring their lessons back at school or college to life.

Peter Ede is an ACIS tour manager from the UK. He has travelled to more than 60 countries and lived in 11 around the world. He is passionate about history, languages and sharing his love for Europe. He is particularly fond of Germany and Central Europe.