A Look Back at the Spark that Ignited a World War

Sarajevo is the capital city of Bosnia and Herzogovina. The country is a fascinating and beautiful place, made up of people of different ethnicities and religions. Think of the land of Heidi: Swiss Alpine like scenery, but often with the white minarets of mosques in the villages instead of churches.

Sarajevo is a city more widely than its relatively small size would ordinarily dictate. It’s known for the longest siege of modern warfare (four years, from 1992 to 1996 during the breakup of Yugoslavia) and before that the 1984 Olympic Winter Games. Perhaps most famously, though, Sarajevo is associated with the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne on 28 June 1914. We are almost 99 years away from that date and will no doubt be hearing much more about it next year.

Sarajevo was always a melting-pot. The Turks had ruled here for centuries, right through until 1878. They left behind them a population of Muslim converts in the heart of Europe. The city was a centre of co-existence: it boasted an Orthodox church, a Catholic Church, a mosque and a synagogue in close proximity to each other.

Next door to Bosnia was the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire: a collection of nations numbering 50 million people ruled by the Habsburgs from Vienna. The Austrians invaded in 1878 and finally completely annexed the country in 1908. Austrian control over this volatile area proved to be fragile. There was an extensive Serbian population, many of whom looked to the neighbouring Kingdom of Serbia and wanted the Austrians out. Years of militant independence acts, or terrorist acts (depending on your viewpoint) carried out by Serbians occurred over the years. Between January 1913 and June 1914 the Austrian chief of staff had recommended war with Serbia some 25 times. This was the “tinder box” of Europe.

Sarajevo was therefore perhaps not the ideal place for the heir to the Austrian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, to visit – and particularly not on 28 June. This was the Serbian National Day: the anniversary of the defeat of Serbia by the Turks in 1389. During that defeat a Serb hero had managed to stab the Sultan of Turkey in his tent. It was the day for Serb patriotism.

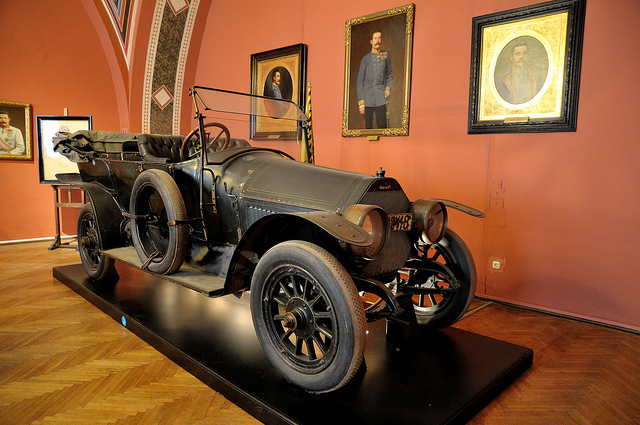

28 June 1914 was also Franz Ferdinand’s 14th wedding anniversary: a sunny Sunday morning. His pregnant wife Duchess Sophie accompanied him on the fateful trip. They arrived by train just before 10am and took an open-top car, registration AIII-118, along the river towards the Town Hall. You can still follow the route, though nowadays the traffic moves on the right whereas back then they drove on the left as Britain still does.

[Photo credit: The Archduke and his family via Flickr]

By all accounts the people of Sarajevo had turned out in force to welcome the Imperial couple. Flags and people lined the route. Only 120 police were on duty and were supposedly more excited in watching the couple pass than on doing their duty. Six young Serbian assassins also hid amongst the cheering crowd. All of their bungled attempts to kill failed. At 10:15, one of them, dressed in a black cape and hat asked a policeman which was the Archduke’s car. Upon being told, he pulled out a bomb and threw it. The bomb bounced off and hit the car behind. It severely wounded two Austrian officers and injured 20 bystanders. The conspirator took poison. It was out of date and he threw it back up, so he hurled himself into the river to drown himself. It was only 4 inches deep. He was fished out and arrested.

The Archduke met the Mayor of Sarajevo and furiously declared that this was a very strange way to greet your visitors: by throwing bombs at them. After a brief reception (the last teacup that Sophie drank from is today in the tiny museum near where she was killed), the couple said they wished to visit the injured in hospital. The Austrian governor suggested altering the route back for safety’s sake, but did not think to tell the chauffeurs.

Accordingly, the car (see above. picture by j-fish) turned into the narrow Franz-Joseph Street pictured below (the original route). The driver was told to stop and reverse back. He stalled the car. Standing five paces away from them eating a sandwich, having given up his attempt to kill and on his way home, was the 19 year old Serbian, Gavrilo Princip. Scarcely able to believe his luck, he tried to pull out his bomb, but because of the mass of people could not. He instead wildly fired two shots: amazingly, both hit their targets with deadly effect. One struck the Archduke in his jugular vein and lodged in his spine. The pregnant Duchess instinctively threw herself over him to protect him: a second bullet went through the side of the car and hit her in the abdomen. His last words were “Sophie, don’t die, stay alive for our children.” She died before he did, just before 11am. Their fateful visit to Sarajevo had lasted an hour.

It later became clear that the Prime Minister of Serbia had been aware of the plans to kill the Archduke. Austria issued an ultimatum on 23 July to Serbia, almost all the terms of which were complied with. Notwithstanding this, Austria invaded on 28 July. A series of alliances and treaties then came into play. Russia went to the defence of its Slavic ally by declaring war on Austria. Germany was bound by treaty to protect Austria, so declared war on Russia. France responded to the German attack on Russia, by declaring war on Germany. Germany invaded neutral Belgium to attack France. Britain, to Germany’s surprise, declared war on Germany ostensibly to defend Belgium. By 6 August a relatively minor conflict between Austria and Serbia, that had begun with two shots, had led to the major powers of Europe being at war.

Many expected it all to be over by Christmas: it was a way of settling nationalistic rivalries on all sides that had been building for decades throughout the 19thcentury. Newly unified Germany was the “new kid on the block” and had become a serious economic and military rival to the old order and power balance, both in Europe and in the colonies. It was not in fact over by Christmas: some 16 million were to die and 20 million to be wounded in the following four years.

The Treaty of Versailles that ended it all put the sole blame at Germany’s hands: a simplistic line that is still trotted out in some quarters today. The French representative at Versailles declared that it was not a peace treaty, but a cease-fire that would last twenty years. How prescient he was: arguably the conflict in Europe that began with that shot in Sarajevo lasted, with some breaks, from 1914, through the Second World War, and into the Cold War, only ending in 1989 in most of Europe, and finally in 1996 here in Sarajevo: some 82 years of conflict.

What happened to Princip? He was a few weeks short of 20 years old at the time he murdered Franz Ferdinand, so was spared the death sentence in accordance with Austrian law. Instead he was imprisoned, where in 1917 the arm that was broken during his arrest was amputated. You can visit the dark, dank, cell number 1 at Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic where he died in solitary confinement, 6 months before the end of World War One, of tuberculosis.

The commemoration of the assassination tells an interesting tale in terms of politics and propaganda. The Austrians erected a twin-pillared monument with crowns on top to the Imperial couple by the bridge adjacent to where they were shot. After World War One, the Austrian monument was pulled down by the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Princip’s footsteps were marked in the pavement where he fired the shots until 1992, when they were removed. There is now a small plaque at the spot on the wall of the small museum to remember the killings.

The Austrians tore down Princip’s house during World Word One. It was re-erected as a museum by the Yugoslavs, for whom Princip was a hero. In 1941 the fascist Croatian Ustashe pulled the house down once more. The Communists then rebuilt it in 1944. It was destroyed for a third time during the recent Yugoslav wars. There are no current plans to rebuild it, unlike the Town Hall where Franz Ferdinand gave his last speech and which is being magnificently restored with EU funds.

The last element of this tale is that curious number plate: AIII-118. A British visitor to the museum in Vienna, where the car now sits, remarked that this was an almost super-natural premonition. It can be taken to read A (for Armistice) 11.11.18 (the date when the fighting in WW1 ended). The Austrian museum curator had apparently not noticed this in 20 years of being there. This is not that surprising, however, given that the German for Armistice begins with a W, Austria left the war on 4 November (not 11 November) and it is fact three letter IS on the plate, not number 1s.

Supernatural it is not, but an undeniable coincidence it is.

Feature photo: [ mhodges]

Peter Ede is an ACIS tour manager from the UK. He has travelled to more than 60 countries and lived in 11 around the world. He is passionate about history, languages and sharing his love for Europe tours. He is particularly fond of Germany and Central Europe.

Peter Ede is an ACIS tour manager from the UK. He has travelled to more than 60 countries and lived in 11 around the world. He is passionate about history, languages and sharing his love for Europe tours. He is particularly fond of Germany and Central Europe.

Interested in history and travel? Download our 5 Trips for History Teachers to see what countries and itineraries made our list.

[button style=”btn-success btn-lg” icon=”glyphicon glyphicon-chevron-right” align=”left” type=”link” target=”true” title=”5 TRIPS FOR HISTORY TEACHERS” link=”http://pages.acis.com/5-trips-for-history-teachers.html”]