Overview

This mountainous province, well known for its folklore, winter sports and beautiful scenery, probably best fits our expectations of Austria. This tiny region was, from the 8th Century BC, a crossroads of Europe. Greek and Etruscan goods were carried over the Brenner, the lowest Alpine pass, and along the Inn valley to the Eastern Alps or West to the Rhine and thence to Northern Europe. In AD 50, Claudius incorporated Tyrol into the Roman province of Rhaetia ruled from Augusburg. In the 4th Century a Roman military base was built at Veldidena, now Wilten, a suburb of Innsbruck, and the area became a bastion against mounting Germanic invasions.

Throughout its history, the province has jealously guarded its independence, but its strategic position has caused it to be used alternately as a punching bag and a bargaining pawn by its more powerful neighbours.

In 550 the Franks took over and throughout the next three centuries the region was continually up for grabs. The Lombards invaded from the South, the Slavs from the East and the Bavarians from the North. The latter cannily established monasteries in the wake of their conquests to win hearts and minds to the Germanic Empire. Charlemagne incorporated the Tyrol into his Empire in 788. By the 11th and 12th Centuries tension between the Emperor and aggressive nobles was such that the Emperor formally gave temporal power to the Bishops. In practise they had to entrust their holdings to the local aristocracy in return for military protection, but the Bishops kept control of the silver and salt mines, mills, customs duties, trade, the minting of coins and the judiciary.

Gradually, however, the nobles unified and consolidated their lands and by the 13th Count Meinhard II ruled an extensive territory and gave it for the first time the name Tyrol, derived from that of his castle in Merano.

Until the end of the Middle Ages, the mining of silver and other precious metals was very profitable in this part of the Alps.

If you look at the map you will find that Merano is now in the Italian province of Alto Adige. This separation of the Sud Tirol from the rest of the province has been bitterly contested many times in Tyrol’s more recent history, and it is the more understandable when you realise that the seat of the very first ruler of Tyrol is now in a foreign country.

Count Meinhard supported Rudolf von Habsburg in his successful war against King Ottokar of Bohemia. This victory was to mark the very foundation of the Habsburgs, power and, by his judicious support, Meinhard won a formidable friend for Tyrol.

The 14th Century was very tough in the Tyrol, as was the case all over Europe. In addition to the plague, however, the locals had to contend with locusts and earthquakes as well as the struggle between the Wittelsbachs and Habsburgs (rulers repectively of Austria and Bavaria) for control of

the Tyrol. Perhaps the story of Frau Hitt (see Innsbruck City Sightseeing) arose as a parable in this period.

By 1342, the Bavarians were firmly in control, notwithstanding the ‘Grosser Freiheitsbrief,’ a kind of Citizen’s Charter for the people. Meinhard’s grand daughter Margarethe thought she could get better conditions from the Habsburgs and in 1363, the Habsburg ruler agreed to protect the Tyrol in exchange for control of communication and trade routes. Unlike the absentee Wittelsbachs, the Habsburgs flattered the Tyroleans by sending the ruler, chosen from a secondary branch of the family, to come and live in the region.

Thus Friedrich IV (The Penniless) resided in Innsbruck from 1420 and things began to look up. In a populist move, he gave the peasants hereditary rights on the land they worked for overlords. Silver mining in Schwaz and salt, the White Gold, from Hall in Tyrol became increasingly lucrative. The inn keepers benefited from the increase in trade and also from an influx of pilgrims, flocking to Rome; and generally the economy began to recover from the calamitous 14th Century.

Friedrich’s successor, Duke Sigismond, moved the mint from Merano to Hall, to be closer to the mines. Unfortunately, he ran through the money like water and lived a wild and extravagant life. Although he fathered 40 bastards, he didn’t manage one legitimate heir. Disaster almost struck in 1490, when he asked the Bavarians to pay off his debts in return for control of the Tyrol. Maximillian, son of the Emperor, saw the danger for Austria (never mind the Tyroleans!) He pensioned off his crazy cousin and took over the reins in 1490.

This is the Maximilian you will be talking about at the Little Golden Roof in Innsbruck. He became Emperor in 1493, but maintained close links with Innsbruck. For one thing he liked the copper and silver mines which provided useful funds for his extravagant projects. Emperor Max also flattered the Tyroleans by giving the people the right to bear arms for territorial defence, a right which they remembered 200 years later on in their history.

Maximillian did, however demand high taxes; his retinue left mountains of unpaid bills, and at one point the city threw them all out. Whether it was this which caused Maximillian to give up his project to be buried in Innsbruck is not quite clear. But it was his grandson who completed the grandiose plans for the spectacular mausoleum in the Hofkirche. Max’s tomb is however empty.

A couple of Ferdinands come next.

You will find Ferdinand II buried in the Silver Chapel upstairs in the Hofkirche. He was a romantic who fell in love with a commoner and insisted on marrying her against the wishes of the Church and the Habsburg family. They were not even allowed to be buried in the same tomb.

Here comes another important theme for the Tyrol: extreme conservatism. This is a common trait of isolated mountain communities of course, but the Tyroleans have brought it to a f ine art. A staunch champion of the Counter Reformation, the Tyrol became known as the ‘Heiliges Land,’ where no religious denomination was allowed other than Roman Catholic.

Tyrol stayed out of the 30 years war (1618-1648) but the economy suffered. The heyday of mining in Schwaz was over by the 16th Century, due to rising production costs and competition from Spanish colonies in the New World.

In 1665 Tyrolean autonomy effectively came to an end, when the Archduke died without an heir. Tyrol came under the direct rule of the Emperor, based in Vienna. The people remained fiercely independent however. In 1703, during the War of Spanish Succession, Bavarian troops occupied Innsbruck. When the Imperial army did not react, Tyrol’s own milita exercised their 200 year old right and drove out the Bavarians on July 26, the feast day of St Anne. Their victory is commemorated in Innsbruck by the Annasaule in Maria Theresa Strasse.

Maria Theresa is fondly remembered in Innsbruck and it is true that the town got an Arch and a Palace out of her. But these were really only to sweeten a bitter pill. In 1749, she had formalised dependency on Vienna, meaning that the Tyrol would have to accept foreign-born rulers. Thus in 1765 it was to flatter the locals that she decided to celebrate her son’s marriage in Innsbruck and built the Triumphpforte.

The Age of Enlightenment left the Tyrol cold. In 1790, the Landtag met, taking its cue form the French Revolution, but instead of proposing new ideas, it repealed the “Toleranzpatent”, passed by the previous ruler the Liberal Joseph II, which had allowed for the formal establishment of religious communities other than Catholic. JosephIs reactionary successors Leopold II and Franz II were much better received!

Tyrol’s bitterest struggle for its independence came during the Napoleonic wars. By this time the province was no longer financially significant to the Habsburgs, and they no longer seem to have had the military will or inclination to defend it. In 1796, 1797 and from 1799 1805 Bonaparte’s armies were in Tyrol. They refused to recognise the militia who were summarily shot on capture. But worse was to follow. After Napoleon’s victory over Austria at Austerlitz in 1805, the Emperor handed Tyrol to his Bavarian allies. The region was renamed South Bavaria a supreme humiliation. The oppressive military regime of the Bavarians provoked open resistance which was heroically led by Andreas Hofer the innkeeper’s son, and hero of the Tyrol. You will be talking about him in Innsbruck, at the Hofkirche where he is buried, and at Bergisel, the site of his four battles against the French and Bavarian armies.

Twice he was successful and controlled the Tyrol as independent Governor. But after each of his victories the enemy returned in force and all appeals to the Emperor for help fell on deaf ears. In fact, after

Napoleon’s victory at Wagram in 1806 Austria’s subjugation was total. By the treaty of Schonbrunn, the Northern part of Tyrol was returned to Bavaria and the South handed to Napoleon’s Italian vassals and incorporated as the province of Alto Adige. Hofer and his men continued to resist, but he was eventually betrayed and executed in 1810. Again the Emperor Franz II made no attempt to intervene, by now he was alarmed at the strength of Tyrolean resistance, and feared the creation of a future separatist movement.

By the Treaty of Vienna in 1815, Tyrol was returned in full to Austria, but Franz was still wary. It was forbidden to celebrate the victories of Bergisel, and no commemorative statue of Hofer was allowed until 1838. The hero’s remains were transferred clandestinely to the Hofkirche, against the wishes of Vienna.

For the rest of the 19th Century, Tyrol retained its historic conservatism. For example, Innsbruck provided a refuge for Emperor Ferdinand when he was driven out of Vienna by the revolution of 1848. Social movements could make no headway and nonCatholic religious schools and congregations were only allowed in 1892.

The outbreak of war in 1914 was met with great patriotism, but heavy losses dampened the enthusiasm and there were strikes and demonstrations in 1918. Italy had remained neutral until 1915, but a secret treaty with France and Britain promised her territorial gains if she entered the war on their side. Thus in 1919, South Tyrol was again given to Italy, a move which one Italian politician admitted was one of ‘sacro egoismo’!

Disillusionment and Depression followed in the 1930’s. The people of Tyrol looked enviously at the regeneration of the German economy under the Nazis, and as early as 1921 voted 98.5% for union with Germany. During the late 30’s the economy suffered from Germany’s restrictions on foreign travel, and by 1938, Tyrol was more than ready for the Anschluss. The German troops were greeted by cheering crowds as they marched in, and there was an immediate upswing in the economy. Centuries of religious conservatism meant that there were few Jews in the Tyrol, and the first feelings of disquiet only came with Nazi attacks on the Catholic Church.

Geographically isolated Tyrol had a relatively quiet war until 1943, when the Allies bombarded ammunition factories and traffic junctions in Innsbruck. American troops marched into Innsbruck on May 3rd 1945, and the town was occupied by French and American troops until 1955 when, along with the rest of Austria, Tyrol regained full independence.

Today the province is still very conservative politically. There have been violent protests over the continued separation of the Sud Tirol in the quite recent past, but these have been somewhat appeased by Italian measures in favour of the German speaking population of Alto Adige. Tyrol today prospers as a haven for winter sports and summer tourists alike.

The History Of Skiing

The Tyrol is one of the oldest winter sports regions in the world. Skis were first brought to the Alps from Scandinavia, where they had long been used for crossing snowcovered landscapes. Early skis were simple wooden boards fixed to leather boots at the toe, leaving the heel free for walking, and similar in this respect to modern crosscountry skis. Sealskins were attached to the base, so that when moving uphill the bristles stuck in the snow giving the skier the necessary grip. Downhill, the fur stayed flush against the ski. Synthetic substitutes for sealskin are still used by crosscountry skiers, along with wax and specially grooved skis.

Early alpine skiers were rich aristocrats and adventurers, attracted by the danger and excitement of the new sport. There were no lifts and no grooming of the slopes. Skiers climbed the slopes in early morning and would attempt one or two runs a day in deep powder snow. There were many injuries and fatalities, and of course no mountain patrols or rescue teams.

In 1901, Hannes Schneider, a native Tyroler founded the Arlberg ski club at St. Christoph on the Arlberg pass above St Anton. He invented the parallel turn, to replace the telemark turn, which required the skier to lean over on the inside ski almost in a kneeling position. Fixed bindings at heel and toe also gave skiers more control of downhill movement but ruled out climbing, so various forms of mechanical lifts were invented. Schneider and the British sportsman Arnold Lunn founded the Kandahar Cup in 1928, which became the unofficial Alpine World Championship race. Previously ski racing had been totally uncontrolled, and had caused some horrific accidents.

Tyrol has twice hosted the Winter Olympics at Innsbruck (1964 and 1976), and is the centre for Austrian winter sports. St Anton, Kitzbuhl and Seefeld are all famous ski resorts, and the Austrian ski school is located at Stams, between the Arlberg and Innsbruck. There is ski jumping at Bergisel, bobsleigh at Igls, skating at Innsbruck and Alpine skiing almost everywhere.

Innsbruck

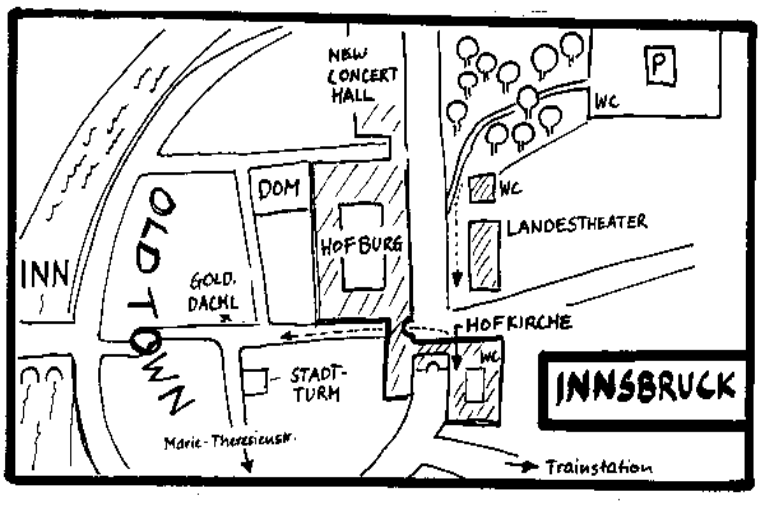

Below is a suggested Walking Tour of the Old Town, which covers the absolute minimum that you should show your group. Depending on the time available it can be combined with any or all of the second section (Innsbruck Sightseeing).

Walking Tour

Start your tour in front of the Tyrolean State Theatre opposite the Hofburg (1). The palace was built in late Rococo style in 1776 by Maria Theresa on the site of the earlier castle. The colour of the facade is known as Maria Theresa yellow, because she liked it. Schonbrunn in Vienna is the same

colour, and whenever you see it in central Europe it’s pretty safe to assume that you are looking at an 18th Century building.

Maria Theresa, the first and only female Habsburg ruler, came to power in 1740. Her father had devoted all his energies to having this unprecedented succession agreed by Austria’s allies and enemies, and had drawn up an agreement known as the Pragmatic Sanction. However, on the accession of the 23 year old Empress (‘with the heart of a king’), the signatories took advantage of the apparent weakness of the Habsburg Empire and moved in for the kill. An entirely unjustified attack on Silesia by the Prussians opened hostilities and the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War, involving most of the European Powers, duly followed.

Maria Theresa proved everyone wrong, however, and was one of the strongest, most pragmatic and best loved of Austrian rulers. In 1745 her husband, Francis of Lorraine, was designated Holy Roman Emperor, continuing the traditional Habsburg right to the title, (which had not been covered by the Pragmatic Sanction), and emphasising the undiminished power of the dynasty. Maria Theresa herself was the perfect prototype of the baroque ruler, with her distinct taste for architecture and interior design, her patronage of music and the arts, and her energetic support of the Counter Reformation. She provided funds for the rebuilding and embellishment of churches and monasteries, and supported the great monastery schools of design such as Wessobrunn. She had 16 children (including Marie Antoinette).

Walk to your left and cross the pedestrian crossing in front of the Hofkirche (2), which is linked to the Hofburg by a covered passage over the road. Take them in for a visit (you pay entrances). From the cloisters, take the door to your right enter the church.

The church was designed and built as a mausoleum for the Emperor Maximilian I, however he is not buried here and the church was built by his grandson, 35 years after Maximilian’s death in 1519. The mausoleum is a spectacular piece of self-glorification. Maximilian took his title of Holy Roman Emperor seriously and wished his name to be linked with the great defenders of Christianity. He therefore designed a tomb for himself to be surrounded by 40 larger than life bronze figures, chosen to emphasise the legitimacy of his power and expansionist ideas.

Only 28 of the “Black Fellows,” as the Innsbruck people call them, were completed. This possibly has something to do with the sculptor Sesselschreiber who seems to have been seriously involved with ‘Wein, Weib und Gesang’ and was eventually sacked and banished to a remote village.

For all this, the monument is highly impressive, and probably the most significant group of German Renaissance sculpture to have survived. Like three dimensional family portraits, the figures claim Maximilian’s illustrious ancestry, and include Rudolf, the founder of the Habsburg dynasty, but also less likely candidates such as Clovis (king of the Franks),

Thoedoric (king of the Ostrogoths) and even King Arthur. Point out the rich costumes, which give a very good idea of the fashions worn by nobles in the 15001s. (The group will also love the shiny bits!) The statue of King Arthur is by Albrecht Durer, and certainly looks very British! A torch could be placed in the right hand of each statue for an additional dramatic effect.

The tomb of Andreas Hofer is at the West end of the church.

Upstairs is the Silver Chapel, so called because of the magnificent silver altar. The chapel was designed by Archduke Ferdinand II to house the tombs of himself and his wife. They are both buried here, he with his armour kneeling beside him, but she is squashed into a niche in the left hand wall because she wasn’t considered noble enough by the Habsburg family.

Leave the church and cross the road to enter the old town. Bordered by the river and surrounded by the Graben (previously the moat outside the city wall), this small area gives a good idea of a closely packed Gothic town.

Walk down the Hofgasse, which is full of little shops, mostly selling souvenirs, until you get to the square. Gather them up in front of the Little Golden Roof (3).

Although the square is small, it was the hub of the medieval town and the largest open space. Here the market would be held and also public festivities, including executions and tournaments. There would be jousting between mounted knights, acrobats, dancers, jugglers, minstrels all the entertainments of the Middle Ages.

The balcony you are looking at has a little roof covered with thousands of gilded copper tiles. Tradition has it that it was built by Friedrich the Penniless because he got fed up with all the bad jokes about his poverty. Actually it was built around 1500 by Maximilian and is another piece of self-advertisement. Max is often referred to as the Last Knight and he and his retinue would watch the colourful festivities from this loggia.

Point out the tumblers and jugglers on the balustrade of the second level. These performers often came from distant lands and were an attraction in themselves. The two central panels are different. On the right, the Emperor is depicted with, on one side a learned advisor and on the other a jester. Next to it you can see Maximilian with his two wives. The lady on the right is Marie of Burgundy. By marrying her Max gained Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and a large chunk of France as well! This was a technique the Habsburgs used often, hence the rhyme:

‘Let others war, thou, happy Austria wed; What some owe Mars, from Venus take instead’

Marie died after a fall from her horse. Maximilian did not appear heartbroken and shortly afterwards married Bianca Maria Sforza of Milan,

the lady in the middle with long hair and an Italian headdress. Through her he acquired considerable territories in Italy.

On the lower level are displayed coats of arms representing Maximilian’s actual and projected acquisitions, each surmounted with a different crown. The double-headed eagle represents the Holy Roman Empire. (Eagles have been popular since the Romans. Napoleon and of course America also chose them as symbols of power).

Take a look around you and point out the pavements covered by arcades good for shopping in snowy winters, and the tall houses with bay windows for maximum light in the narrow streets. The pile of whipped cream on the corner to your left is the Helblinghaus (no 4). It has obviously had a spectacular makeover in the heyday of 18th Century Rococo; a fine example of bourgeois ostentation.

Take the street to your left, which leads to the river. You will pass the Goldener Adler Inn (no 5), which has been in business since the 1500’s. The names of its distinguished guests, from Goethe and Paganini to film stars and politicians, are displayed on a plaque outside.

Walk down to the bridge over the Inn. Innsbruck means “bridge over the Inn” and the town goes back at least 800 years, since the time a little chapel was consecrated to St Jakob the Traveller, in the forests by the river Inn. Your next stop will be at the Cathedral which now stands on the same spot. Looking across the river you have a view of the Nordkette range of the Karwendel Mountains. Away to the right, the Hungerburg cable car provides easy access to skiing in winter or summer walks on the mountain trails.

Walk along the river and take the first turn to the right which will lead you to St Jakob’s Cathedral (no 6). Built in 1720 on the site of the 1180 Gothic church which was badly damaged in an earthquake, the interior is a fairly modest example of the Baroque. Don’t overdo it if you are going later to the Wilten Churches which are much more impressive. The trompe l’oeil ceiling is however positively dizzying and a good illustration of the baroque technique of drawing your eye up by a series of false perspectives until you lose yourself in a heavenly vision. The pride of the Cathedral is the painting displayed on the Altar by Lukas Cranach the Elder. It depicts Our Lady of Succour (Mariahilf), and is an object of deep devotion, copied many times over on the facades of houses in the Tyrol. The canopied tomb in the North transept is that of Archduke Maximilian II, who died in 1618.

Walk back to the square along the Pfarrgasse. Depending on your schedule, you can give f ree time at this point, for shopping, lunch etc. You could suggest that they climb up the Tower of the Old Town Hall (no 7) for a nice view. Otherwise, take them back to the bus and continue your sightseing.

Innsbruck Sightseeing

This includes the Wilten Churches, Bergisel, the Ski Jump and Maria Theresien Strasse from the Triumph Arch to the old town. Be aware that this last is probably impossible to do on your bus. You could drop them at the Arch and walk together to the Graben. You can pick up the bus again on the bus park.

Ask your driver to take you to the Wilten Churches (follow signs to the Brenner) and to park at the Basilica (the yellow one). Be warned that either or both of these churches may be closed, but it is worth at least trying to see the Basilica.

Your group may have some knowledge of Gothic Cathedrals, but Baroque and Rococo Church architecture often comes as a bit of a surprise. You should give them an idea of the reasons for the changes in the way people wanted their churches to look. Gothic mysticism and unquestioning faith were out by the 18th Century. They will see no stained glass, no soaring columned naves. The Reformation of the 16th Century and the Thirty Years War which followed, changed people’s perceptions of the Church for ever. on the one hand the Protestants reacted to the splendours of the Renaissance and the decadence of the Papacy, both in their revised liturgy and in their churches. The fresoes were whitewashed over, the statues defaced or removed altogether, so as not to distract the mind from prayer.

The Jesuits, on the other hand, wanted to win people back to the Catholic Church and put every effort into making their churches as magnificent and ornate as possible. The accent was firmly on theatrical effects. A typical Baroque church is decorated in a series of levels, starting with unadorned pillars, and rising through different levels of ornamentation to the magnificent trompe l’oeil painting on the ceiling. Windows are always of plain glass, and are placed high up, in order to illuminate the heavenly scene. Many churches were however, merely baroque-ised, with ornamentation being added to the original structure.

It is often said that there are no straight lines in the Baroque style. Circles have become ovals, angels have become cherubs and everything is covered in magnificent coloured scrolls of stucco. The effect is easy to appreciate and there is a powerful appeal to the emotions. As time went by, Baroque became more and more exaggeratedly ornate and is called Rococo (the word comes from the French rocaille) and is typified by sinuous stucco work resembling corals or seaweed.

The Basilica was restored between 1751 and 1756, by the Wessobrunn Abbey school of art in Bavaria, and is one of the finest Rococo churches anywhere. Give them a few minutes to admire the interior; and then walk them across the road to the Abbey Church (the red one). If it is open, take them inside. The decoration was completed in 1670, 80 years before the Basilica they have just seen and is definitely less exaggerated. The stucco is uniformly white, instead of the pastel shades of Rococo, and the black, white and gold theme has a starker dramatic effect.

Even if you can’t go in, you can tell them the story of the giants, whose statues stand outside the entrance. You might wonder what they are doing outside a church. Their story has to do with the legendary founding of the Abbey and is a nice mixture of pagan superstition and pious Christian belief.

On the left we have Aymon from the Rhine Valley in Switzerland. on the right is Thyrsus, from the Zirl mountains just outside Innsbruck. They met up here and had a ferocious fight in which Thyrsus was killed. His blood flowed into a little stream, where even today a medicinal plant can be found called Thyrsus.

Our Swiss giant Aymon felt deep remorse and decided to atone for his deed by building a monastery on this very spot. He worked hard to drag the great stones from the mountains, to shape them and build them into walls, but every morning he would find his work of the previous day destroyed. The nasty local dragon, who didn’t want a monastery on his patch, crawled out of his cave every night and destroyed the walls with mighty blows of his tail. One night Aymon lay in wait f or the dragon, and f ought a terrible battle with it. He was victorious and after he had killed the dragon, cut out its tongue (as giants do). He finished the Abbey in peace and then threw a huge rock with all his strength. As far as the rock flew the land belonged to the Abbey and was free from trouble and sorrow. He then entered the Abbey and died after a pious life in 878. According to legend he is buried under the altar with the dragon’s tongue.

Back on the bus and head up to Bergisel. There is a sharp turning to the left with a sign pointing to Bergisel. When the road forks, take the left, which brings you to the statue of Andreas Hofer and signs for bus parking.

Every country has its hero and freedom fighter and Tyrol is no exception. The Tyrolean peasants, under the leadership of Andreas Hofer, defended their country here four times against the French and Bavarian invaders during the Napoleonic wars.

Whereas they could have expected assistance from the Austrian Imperial Army, they were left to fight it out alone. Ill equipped and trained, their sole advantage was their passionate patriotism combined with an unmatched knowledge of their mountain terrain. Although he was eventually betrayed and executed by firing squad, his powerful personality lives on in this imposing statue which was made with bronze from captured French canons.

Walk to the ski jump. The winter Olympics came to Innsbruck in 1964 and again in 1976 and transformed the town into an internationally known winter sports centre. A great deal of money went into building new facilities like the Olympic ice stadium, swimming pool, entertainment hall and a lot of new roads and bridges. These are all made good use of, and every winter the international skijumping competition is held up here on Bergisel. There is a bronze plaque bearing the names of the Olympic winners of 64 and 76 at the end of the landing area.

Discourage people from climbing to the takeoff platform unless you really have a lot of time. You have a splendid view in any case over the town and the mountains beyond, and you might want to tell them the story of Frau Hitt.

In times before history, when a race of giants were lords over the Inn river valley, the giant queen Frau Hitt ruled over a fertile and prosperous land of cornfields and fruit orchards where Innsbruck now lies. She was a proud and cruel queen, not much loved by her subjects. one day her young son Hagen came wailing to her, all covered in mud and slime. This wild young giant had taken it into his head to break down a pine tree in order to carve himself a rocking horse, in spite of the warnings of the wise wood giants, who knew that the forest was sacred and should not be damaged. Hagen had bent the pine tree down to the ground, but it would not break. Instead it catapulted back with such force that Hagen was f lung through the air and landed in a swamp. Frau Hitt, instead of reprimanding her son for his wilful impiety, ordered her servant to clean off the mud with soft breadcrumbs a second and even more dreadful impiety, for bread is God’s gift to man and should not be messed with if you know what’s good for you. Scarcely had the sacrilege begun when a terrible storm broke; mighty thunder roared through the mountains and soaring flashes of lightning ripped across the heavens. When the sky became light again the rich cornfields and fruit orchards were transformed into a desolate wilderness of towering rock, and on top of the mountain, transfixed for ever in stone as an eternal reminder of her impious pride, is Frau Hitt with her boy in her arms.

Try to point out Frau Hitt. There is a long sweeping dip in the line of the mountain peaks broken by two peaks close together in the middle of the dip. Just to the left of these two peaks is a small but obtrusive knobbly jutting rock that, if you exercise a lot of imagination, could maybe look a bit like a figure with a crown, carrying a child. This is Frau Hitt, 2272 metres high.

Get everybody back on the bus and drive back down to the town.

When you get to the Triumphpforte, ask the driver to drop you and carry on to the bus park where you will meet him later.

In 1765 all the court was in Innsbruck to celebrate the marriage of Maria Theresa’s son Leopold to the Infanta Maria Ludovica of Spain. The impatient lover went to meet his bride on the Brenner pass and caught a cold. He made it through the ceremony, but immediately afterwards was carried to his bed, where he lay seriously ill with pleurisy and fighting for his life. The court waited patiently and when the prince was out of danger, the festivities started. Unfortunately, Leopold’s father Francis, the much loved husband of Maria Theresa, succumbed in his turn.

Whether he caught his son’s cold, wore himself out partying or simply died of a heart attack, no one knows. Two years later a still broken-hearted Maria Theresa had this arch erected to commemorate, on one side the

joyous event of her son’s marriage and on the other the tragedy of her husband’s death.

Walk down the Maria Theresienstrasse until the Annasaule (St Anne’s column). This commemorates the victory of the Tyroleans over the Bavarians on July 26th (St Anne’s day) 1703. The Virgin Mary stands on the column and St Anne is down at the bottom together with St George the dragon slayer and protector of the Tyrol.

This is the best spot in all Innsbruck for a photograph, with the mountains in the background, but watch out for the traffic.

Continue down towards the old town. The street is lined with prettily coloured houses, and has all the everyday and (slightly) less expensive shops. Once across the Graben it’s straight on to the Little Golden Roof and territory that everyone knows.